The Wall a novel by Nathan Wisft

Reviewed by Paul Zakaras

23 May 2016

“Nightmare land down there, ol’ buddy,” a character in Nathan Wisft’s sci-fi novel, The Wall, tells his lover. “Power going off, sewers bubbling up, and that bad chicken’s giving folks the runs. Everybody’s looking to shoot someone. Even school kids are packing, and teachers been ducking fast under their desks.”

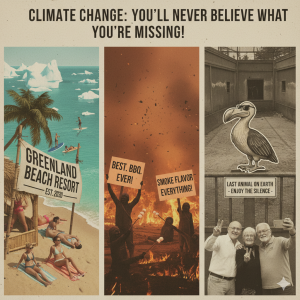

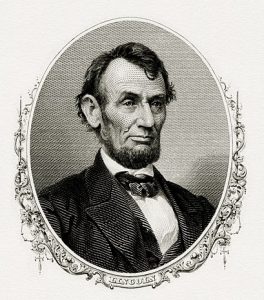

The speaker is referring to a dilapidated country called the Grand Union of Free States that was established after the South’s victory in the Civil War. The year is 2030, but GUFS has stuck to its core principles and remains a slave state that’s separated from America by a long, Berlin-like wall running along the old cease-fire line from Virginia to the Rio Grande. Built to keep slaves from escaping, the wall has been falling apart for decades, and when the maintenance burden becomes unbearable for the impoverished GUFS, it negotiates a transfer of rights to the New United States.

At first the NUS is content with patching and painting. But public pressure—“If you fix it, they won’t come”—soon has Washington acting to stem the flow of illegals from the south. Robot construction gangs under the direction of billionaire builder Elver Shoat reinforce the wall along its entire winding route. “It’s a beautiful wall now,” Shoat boasts. “An amazing wall. A wall that’ll last a thousand years, I guarantee it. Believe me, a thousand years or your money back.”

Despite Shoat’s promises, the wall turns out to be less than perfect, as illegals still find ways to cross. “Sure,” the White House press secretary concedes, “you’ve got people digging tunnels like moles. But we pounce the minute they surface. And if you’re black or brown, fine, you probably get asylum. But if you look white and you can’t pass our basic science test, you’re gone.”

The body of the novel is a first-person account related by Lieutenant Bud Grant, a border control officer whose job it is to screen white illegals. All of them tell the same story: they’ll be beaten toothless by government skinheads if they’re sent back. But since they offer no supporting proof for these claims, a reluctant Bud has to turn their pleas aside.

Bud’s unease about his role as judge comes to a head when he’s confronted by handsome, charming Chauncey DeForest, the disinherited ninth son of “General John” DeForest, whose megafarming conglomerate buys and sells hundreds of thousands of slaves each year. Chauncey ridicules the very idea of evolution and admits he’s worn a trucker’s cap much of his life, but still insists on asylum because he’s gay and fears flogging and imprisonment for violating the South’s so-called “Saudi laws.”

After hours of talk, Bud, a gay man himself, signs the order that admits Chauncey into America and welcomes him into his life. At first, their relationship doesn’t seem promising: “You keep trying to turn me into a nice, middle-class partner,” Chauncey yells during one of their earliest fights. “But I’ll always be a white supremacist, you understand? And I’ll never believe Adam was a monkey. So if you really love me, love me for who I am, not this vanilla person you’d like me to be.”

Bud’s loving patience—“It’s like trying to tame a wild horse,” he thinks, “you want to do it, but in a way you don’t”—makes gradual inroads. But the growth of their relationship is interrupted by an unlucky event that takes the lovers over to the wrong side of the wall.

Although Chauncey’s “nightmare” lines warn readers early on that GUFS wouldn’t make an ideal travel destination, the truly chilling nature of Wisft’s dystopia isn’t revealed until Bud risks his career and even his life by crossing into the South. Chauncey, it turns out, has been caught buying banned drugs, cycled quickly through Alien Deportation Court, and sent on his way. Bud arrives too late with an official pardon and can only watch as Chauncey’s driverless bus departs.

The remainder of the book is mainly the story of Bud’s quest for his true love. Rumors about Chauncey’s whereabouts push Bud deeper and deeper into a future South, offering glimpses of what life in the fictional GUFS has become. Here, unfortunately, Wisft’s plate fails to offer much more than warmed-over Dixie fare. Bud witnesses the horsewhipping of an abortion doctor, watches prisoners in a chain gang collapse under the blazing Texas sun, gazes over vast fields of cotton tended by bent slaves. And so on, page after predictable page.

When Bud finally locates the abused Chauncey in a New Orleans brothel and frees him at gunpoint, the lovers make a wild break for the safety of the north. What follows is a series of walpurgisnacht chase scenes: naked, tattooed “wildhairs” racing after the fugitives on giant motorcycles, a shotgun-blasting rural sheriff tracking them with a pack of yelping hounds. Most terrifying of all are the Swastika-banded descendants of wealthy Nazi settlers permitted to conduct medical experiments on anyone they take alive.

Passing himself off as a “certified purveyor” of genuine dinosaur eggs, Bud bribes a greedy preacher, Bishop Bob, into letting Chauncey hide in his church. But when the eggs turn out to be cheap plastic imitations stolen from a roadside attraction, the livid bishop alerts the Aryan Squad. The book closes with a final desperate chase: Bud and Chauncey running all night through a snake-infested swamp and reaching the foot of the wall just as the posse of blond scientists emerges from the woods and orders them to “halt.”

The dystopian worlds imagined by sci-fi misanthropes are usually black holes from which nothing good can escape. Yet the brave love between the stolid Bud—weighed down by low self-esteem and existential doubts—and the mercurial, guilt-free Chauncey, seems worthy of a happy ending. Of course the hand that holds out the morsel of hope can also snatch it away. And it will come as no surprise to veteran readers of science fiction that Wisft remains true to himself to the final page.

NOTE: Nathan J. Wisft began his career by authoring children’s stories in the manner of the Brothers Grimm. After turning to science fiction in his sixties, he has published such cult classics as Gullible Travelers, The Night of the Lotus, and A Stopwatch Lemon. He is currently at work on a political satire tentatively titled Death and Texas.

Paul Zakaras has taught literature and writing classes at the University of Maryland, Santa Monica City College, and several other institutions. Currently he’s writing innovative book reviews, original obituaries, and imaginary biographies. He expects to continue in this vein until someone tells him to stop.

Be First to Comment