South from Granada by Gerald Brenan (1957).

As a teenager in the British Army, Gerald Brenan won a Military Cross in World War I. His soldier’s pension allowed him to escape from an unhappy love affair and to live for seven lonely years in the remote mountain fastness of Yegen, a village in southern Spain. Brenan went to Spain to educate himself and to write, and became deeply attached to the timeless atmosphere of the village and to its magnificent views of the mountains and the sea. Brenan traveled on foot throughout the country and once shared a train carriage with a flock of sheep.

In a clear, engaging style he describes the fragrance of olive oil, leather and dust, the folklore, festivals, people, quarrels and love affairs. He portrays himself as rough, earnest and independent; as improvident and extremely poor. Friends from England, including philosopher Bertrand Russell and writer Virginia Woolf, both visited. The arrival on muleback of the frail writer Lytton Strachey was alarming and amusing: “his stomach was delicate, Spanish food had disagreed with him, and he was not feeling in the mood for adventures.”

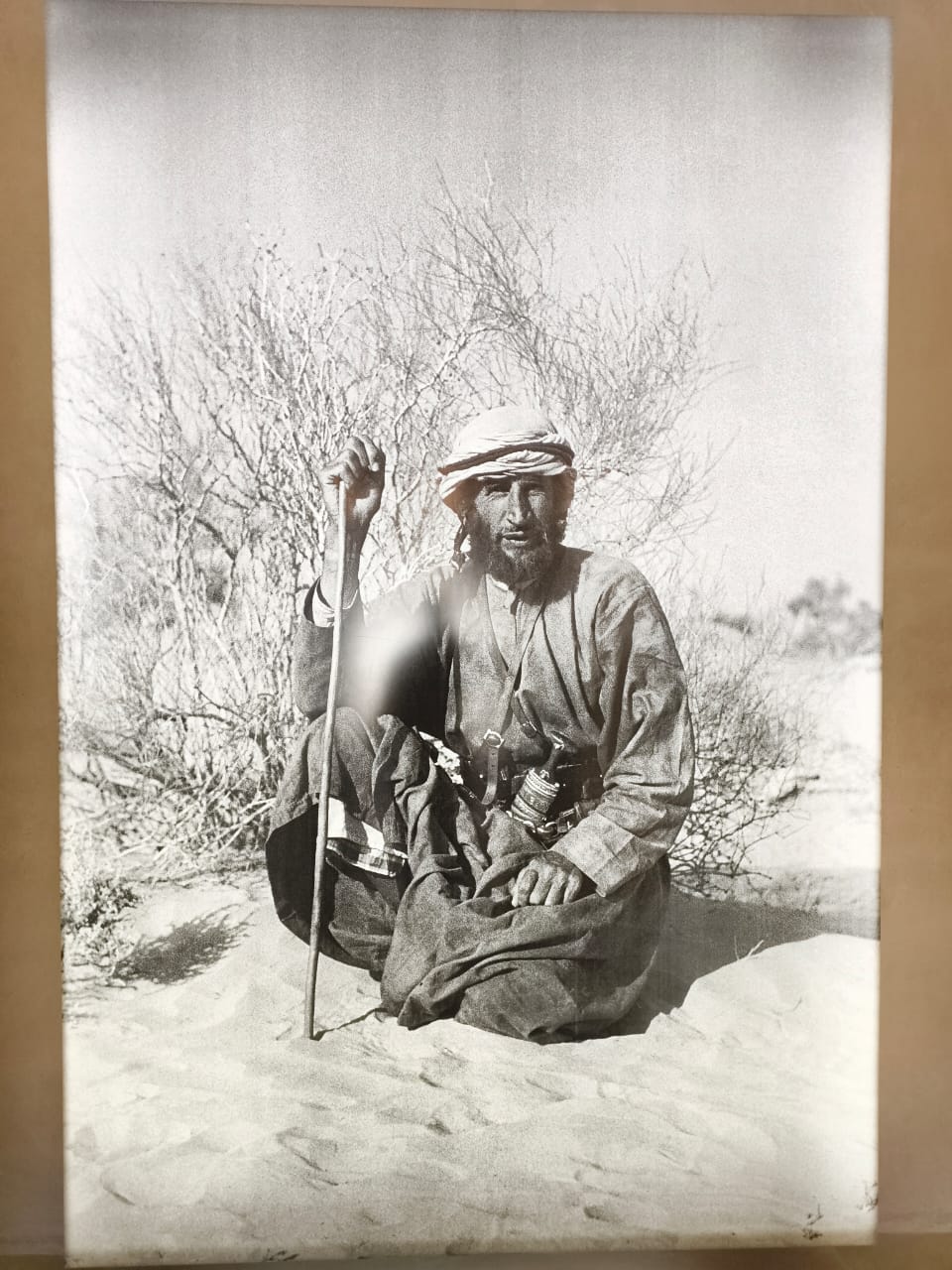

Arabian Sands by Wilfred Thesiger (1959).

“I craved the past, resented the present and dreaded the future,” said Wilfred Thesiger. Fascinated by tribal people and remote landscapes, the British explorer and writer saw travel as a masochistic challenge. “Arabian Sands” describes his four crossings of the desolate Empty Quarter of the Saudi Arabian peninsula between 1945 and 1950. Compelled to go where others had never been, Thesiger wanted to submit to the “perverse necessity which drives me from my own land to the deserts of the East.” For him travel was about finding resolution and enduring pain: “Journeying at walking pace under conditions of some hardship, I was perhaps the last explorer in the tradition of the past.”

He emphasizes the windswept austerity of the desert, “infinitely remote from the world of men.” He eagerly endured fiery heat, cold nights and constant fatigue; thirst and starvation alleviated by disgusting food, while his agonized feet cracked from the cold. Thesiger defines and authenticates his torment, and shows how suffering can become an ecstatic pleasure. A lyrical passage describes his attraction to the desert: “the mountains on either side are often beautiful, especially at dawn and sunset when borrowed colours soften the austerity of rock and sand, but they are seldom touched with green. Usually the few camel-thorns, which throw a thin mesh of shadow over the darkly patinated rock, rustle dryly in the breeze. But on Jabal Qarra the jungle trees are wreathed with jasmine and giant convolvulus and roped together with lianas.”

Travels with Myself and Another by Martha Gellhorn (1978).

The journalist Martha Gellhorn accepted an assignment in 1941 from Collier’s magazine to visit China, then fighting a war with Japan. Gellhorn and “Another”—her husband Ernest Hemingway—began in Hong Kong and endured a rough journey for thousands of miles by horse, car and boat. In Chungking, the wartime capital, Gellhorn interviewed the Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek and his Wellesley-educated wife. The Generalissimo, who was “thin, straight-backed, impeccable in a plain grey uniform and looked embalmed,” feared the Communists more than the Japanese.

The high point of her trip was a secret meeting in Chungking with the revolutionary Zhou En-lai, living underground and in constant danger, “the one really good man we’d met in China.” Zhou accurately predicted that there would be a civil war in China and that the Communists would be victorious. Gellhorn found China “absolutely exhausting and appalling and discouraging and dreary because there are four hundred million people who live worse than animals and in a state of filth and disease to break your heart.” During her “unsurpassable horror journey,” she saw the Chinese as a mass of downtrodden, doomed but valiant humanity.

An African in Greenland by Tété-Michel Kpomassie (1983).

Born in tiny, tropical Togo in 1941, one of 27 children, Tété-Michel Kpomassie was inspired by a schoolbook about Greenland. Working for eight years through West Africa and Europe, in 1965 he finally reached the largest island in the world, which had only about 33,000 people. Some children in Greenland screamed when they saw him, adults were fascinated and hospitable. During his 18-month-long stay as an observer he ate seal blubber and the raw flesh of dogs and birds. Kpomassie notes the odd sense of humor: “the tendency to ridicule people [including the author] is one of the qualities Greenlanders most appreciate.”

As winter approached some locals suffered from polar hysteria, and alternated between listlessness and unbridled fury. Kpomassie’s writing can be savage and lyrical. On an ice-fishing expedition, “we slashed the shark open with a knife, giving him part of his own entrails to chew on . . . to prevent him from trying to bite any of us.” During September’s first snow, so thick were the snowflakes that it seemed “all the white birds in the world were shedding their feathers

Between the Woods and the Water by Patrick Leigh Fermor (1986).

In 1933, after being expelled from school, Patrick Leigh Fermor set out to walk across Europe, passing through nine countries: Holland, Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. His yearlong, 1,700-mile ramble—rough when he was solitary and poor, hedonistic as frequent guest and lover—was a feat of social and cultural exploration. Fermor’s serpentine, even baroque writing style clashes with his more realistic and austere descriptions of colorful gypsies and cave-dwelling bandits. In the wilds of Romania he met the Skopzi, adherents of a religious sect who “castrated themselves to achieve a closer union with God.” In Romania Fermor also met many intriguing down-at-heel aristocrats, bored on their crumbling country estates, their way of life doomed to extinction by World War II. They welcomed the well-read and entertaining young man into their castles and libraries, where he indulged his curiosity about genealogy, his capacity for drink and sexual desires. His principal lover was a Romanian princess, Balasha Cantacuzene, whom he called “so fresh and enthusiastic, so full of colour and so clean.”

Jeffrey Meyers published James Salter: Pilot, Screenwriter, Novelist and Parallel Lives: From Freud and Mann to Arbus and Plath last year. Forty-Three Ways to Look at Hemingway will appear in November, The Biographer’s Quest in April 2026.

Be First to Comment